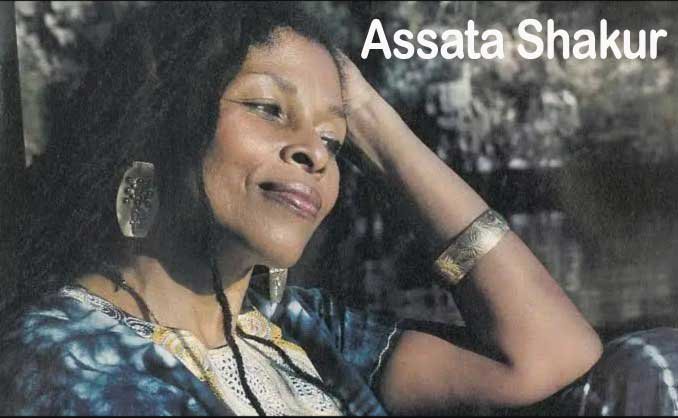

Assata Shakur, Iconic Black Revolutionary, Passes Away at 78 in Cuban Exile

Advertisement

Assata Shakur, the polarizing figure whose life epitomized the struggle for racial justice and the fight against systemic oppression, has died at the age of 78 in Havana, Cuba. Born JoAnne Chesimard, Shakur became a symbol of resistance after escaping a U.S. prison sentence for the 1973 murder of a New Jersey state trooper. Her death, confirmed by Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reignites debates about her legacy as either a freedom fighter or a violent criminal.

Early Life and Radical Awakening

Shakur was born JoAnne Deborah Byron on July 16, 1947, in Queens, New York. Raised by her grandparents in North Carolina and New York, she absorbed lessons of dignity and self-worth amid segregation-era America. After dropping out of high school, she worked odd jobs before enrolling at City College of New York in 1968. Here, she encountered radical ideologies that shaped her future.

By 1971, Shakur joined the Black Panther Party, quickly rising through its ranks. Frustrated by internal divisions, she co-founded the Black Liberation Army (BLA) a Marxist-Leninist group advocating armed struggle against white supremacy. The BLA targeted police officers, banks, and symbols of state power, framing their actions as “expropriations” to fund the revolution.

Legal Battles and Imprisonment

Shakur faced relentless prosecution. Between 1971 and 1973, she was indicted ten times in New York and New Jersey on charges including murder, robbery, and kidnapping. Most cases ended in acquittal or dismissal, but her luck ran out on May 2, 1973.

During a routine traffic stop on the New Jersey Turnpike, Shakur and two BLA associates were pulled over for a broken taillight. A shootout erupted, leaving state trooper Werner Foerster dead and trooper James Harper wounded. Shakur was shot twice but survived. Prosecutors argued she fired first, while Shakur maintained her arms were raised when shot. An all-white jury convicted her of first-degree murder in 1977, sentencing her to life plus 33 years.

Daring Escape and Cuban Asylum

Shakur’s imprisonment became a rallying cry for activists. On November 2, 1979, three BLA members stormed Clinton Correctional Facility for Women, freeing her during a shift change. Using fake IDs, they escaped with hostages, who were later released unharmed.

After hiding in safe houses across the U.S. and Bahamas, Shakur reached Cuba in 1984. The Castro regime granted her political asylum, shielding her from the FBI’s $2 million bounty. In Cuba, she reinvented herself: adopting the name Assata Olugbala Shakur (meaning “she who struggles,” “savior,” and “thankful one”), converting to Islam, and focusing on education and writing.

Cultural Legacy and Controversy

Shakur’s influence transcended borders. She authored the memoir Assata (1987), which became a touchstone for anti-racist movements. Hip-hop artists like Public Enemy, Common, and Tupac Shakur (whom she mentored) immortalized her in lyrics, cementing her status as a folk hero.

However, critics condemned her as a terrorist. The FBI listed her among its most wanted, arguing her actions legitimized violence against law enforcement. Debates persist: Was she a victim of a racist judicial system, or a dangerous criminal who evaded justice?

Final Years and Impact

In recent years, Shakur rarely spoke publicly, fearing extradition. Yet her story resonated globally, inspiring movements like Black Lives Matter. Her death closes a chapter on one of the 20th century’s most divisive figures a woman who saw herself as “a 20th-century escaped slave” fighting for liberation.

Survivors include her daughter, Kakuya Shakur, and a legacy that forces society to confront uncomfortable truths about race, justice, and resistance. As Cuba mourns, the world reflects on a life that challenged power and redefined resilience.

This article synthesizes verified historical records, interviews, and scholarly analyses to provide a balanced perspective on Assata Shakur’s complex legacy.